Cost Effects of IT-Enabled Projects

"Life is a perpetual instruction in cause and effect."

Ralph Waldo Emerson

- There are 5 ways in which IT-enabled projects affect an organisation's costs:

- Cost savings. Cost reductions from removing costs

- Cost avoidance (economies of scale). Cost reductions from improving efficiency (and therefore output).

- Cost structure. Changing the mix of fixed and variable costs.

- Cost assignment. Tracing, rather than allocating, costs.

- Economies of scope. Sharing of costs across multiple product/service offerings.

Business cases for IT-enabled projects are often built around cost savings. However, projects can affect an organisation's costs in another four ways.

Understanding these five effects is important because all of them should be considered when preparing business cases, although not all are applicable to all projects.

1. Cost Savings

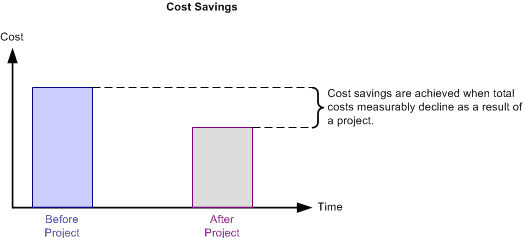

Let's start with the most obvious cost effect, cost savings, which are illustrated below.

Most business cases include some level of cost savings but including these is a double edged sword: cost savings are easy to include, but hard to realise.

The reason cost savings are hard to realise is two-fold:

- Failure to take costs out. Costs are reduced only if they're taken out of the system (the business unit, the process, the product). If a department had an annual budget of $5 million and a business case proposed cost reductions of $500k, that department should only need a budget of $4.5 million next year. It's that simple, but it rarely happens. In most organizations, that department will still get the $5 million, arguing that the project did indeed deliver the $500k in savings, but those savings have been 'reinvested' (e.g. the people that were doing work that became redundant were redeployed to different work). Freeing people up to do different (hopefully productive) work is certainly a benefit, but it is not a cost saving (you're still paying the redeployed people and your costs haven't changed).

- Poor cost visibility. Eliminating costs which span organisational boundaries, budget centres and reporting lines is possible but for two reasons it rarely happens. Firstly, while many people may be responsible for reducing costs, no one person is accountable for ensuring it happens. Secondly, most organisations don't have sufficiently advanced management information systems to be able to track costs that span budget silos (e.g. organisations can't tell you how much the order-to-fulfilment process costs per order).

For these reasons, the cost savings listed in business cases should probably be reclassified as cost avoidance, rather than cost savings.

2. Cost Avoidance (Economies of Scale)

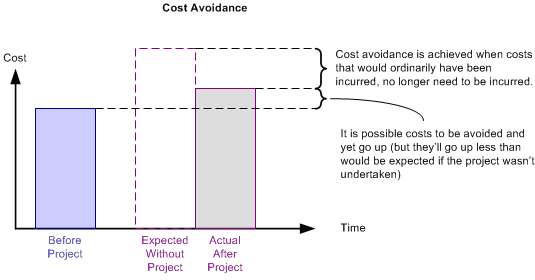

The key difference between cost savings and cost avoidance is that the latter doesn't

actually reduce costs. As the diagram below shows, it is possible for total costs

to actually go UP even as costs are avoided.

There is a very good reason to include cost avoidance in business cases: cash flow.

Cash-flow problems can bankrupt even a highly profitable company and there are only

two ways to improve cash flow:

- bring in cash as fast as possible

- delay paying cash for as long as possible.

Cost avoidance essentially delays expenses, leaving cash in the company for longer, and thus improves cash flow.

Project Example: Cost Savings vs. Cost Avoidance

Implementing an Interactive Voice

Response (IVR) system which prompts callers to select their reason for calling and

enter their customer number.

There will be cost savings because the customer is connected to the person most qualified to help (no time wasted redirecting customers)

and because the customer service person won't waste time asking for a customer number

and searching for the customer's record. The company has a choice about what to

do with those time savings:

- Cost reduction: Since each call now takes less time, it may be possible to reduce the number of staff in the contact centre.

- Cost avoidance: Instead of reducing staff numbers, the company may decide that the time saved is enough to conduct a cross-selling/up-selling campaign without increasing staff numbers in the call centre.

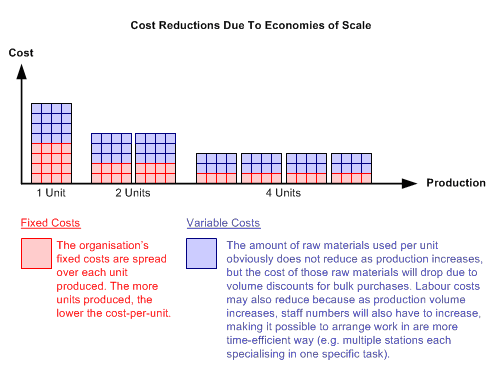

The concept of cost avoidance is closely related to the concept of economies of

scale. Economy of to scale refers to the reduction in per-unit costs through increased

production, as illustrated below:

The diagram above shows that these cost reductions come from two areas:

- Reduction in variable costs.Variable cost can be reduced through volume discounts

on raw materials and increased specialisation of labour.

- Spreading fixed costs across more units. By spreading the cost of the factory across 100,000 widgets instead

of 10,000, you'll drop the cost-per-widget ten-fold.

By increasing efficiency, it means that production can increase without an commensurate

increase in costs.

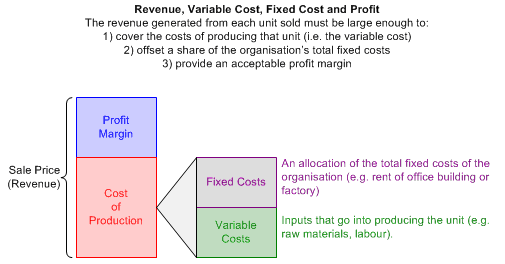

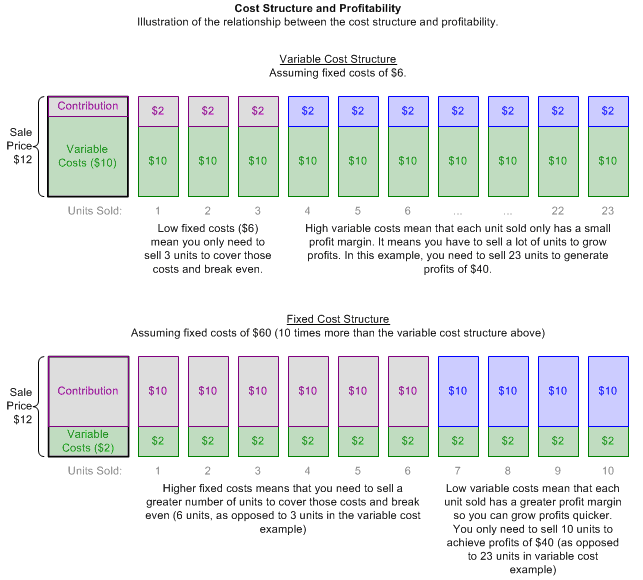

3. Cost Structure

One way of classifying costs is according to their behaviour relative to production

output [1]:

- Fixed costs: fixed costs do not change in response to changes in output. For example,

the cost of a factory WILL NOT change whether you produce 10 widgets or a million

widgets.

- Variable costs: variable costs change in response to output. For example,

the cost of raw materials WILL increase if you increase production from 10 widgets

to a million.

The mix of fixed and variable costs, is known as the organisation's cost structure.

The ideal structure depends on the unique circumstances of each individual organization

– there is no one 'best' cost structure.

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between revenue, costs and profits:

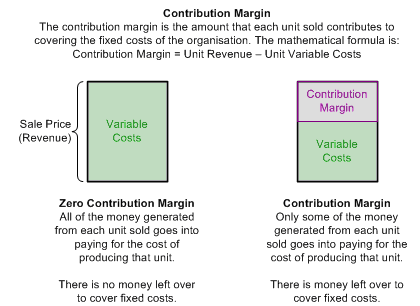

The relationship between cost structure and profits is explained by the concept

of "contribution margin":

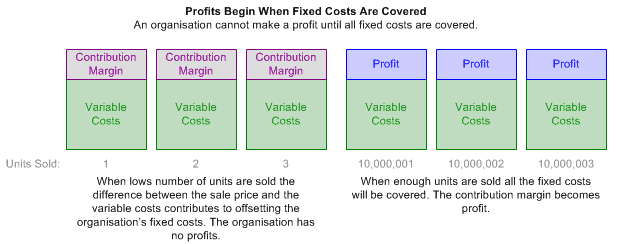

As the following diagram illustrates, there are no profits until all of the organization's

fixed costs are covered.

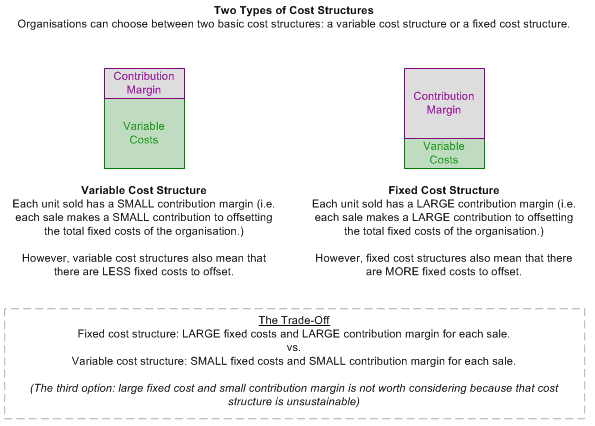

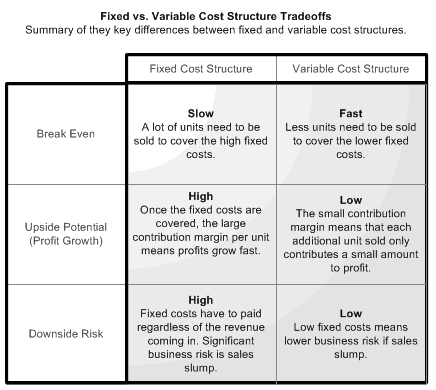

The organization basically has a choice of two cost structures:

So how does an organization choose between the two cost structures? It basically

comes down management's prediction of sales volume:

In summary then, management considers the following trade-offs, makes a prediction

about sales volume and then organizes the cost structure accordingly[2].

So what has all this got to do with IT-enabled projects? In a nutshell: projects

can affect the cost structure of an organization. They can:

- Convert fixed costs to variable

- Convert variable costs to fixed

Understanding how a proposed project will affect the organization's cost structure

is critical because it must be in full alignment with management's strategic direction.

Side Note

It's important to point out that cost cutting and efficiency initiatives

are a separate issue to choosing the cost structure. Regardless of which cost structure

is chosen, cost reductions must happen in both types of costs (i.e. just because

you choose a fixed cost structure doesn't mean you only eliminate variable costs,

and vice versa).

Converting Fixed Costs to Variable

Given the turbulent economic times (November 2011 as I write this) it's not surprising

that many organizations are moving towards a variable cost structure. As illustrated

earlier, a variable cost structure protects you from downside risk (lower fixed

costs mean you need less sales to cover them). It is easy to scale costs up or down

in response to fluctuating demand for products and services.

Project Example: Converting Fixed Cost to Variable

Outsourcing projects are often seen as a mechanism for cutting costs but they are also ways of converting fixed costs to variable. If, for example, you want to scale your call centre up or down it is a lot easier to increase or reduce capacity if the call centre is run by a third party than if you had to do it internally. Some outsourcing services charge 'per transaction' and this is the ultimate in variable cost (e.g. per invoice sent, per phone call handled).

Converting Variable Costs to Fixed

While cautious organizations convert their fixed costs to variable in order to protect

themselves from downside risk, other organizations look to capitalise on upside

potential (even making capital investments and expanding during recessions to get

a jump on the competition when the economy starts to recover).

The "fixed vs. variable" decision is really about the expected volumes of output

and management's tolerance of risk. The higher the expected volume, the greater

the justification for fixed costs – but the greater the risk if volumes don't meet

expectations.

Project Example: Converting Variable Cost to Fixed

Projects that reduce transaction costs convert variable costs to fixed. For example, you could increase the size of the contact centre to handle increased call volumes as the customer base grows (the variable cost approach). Alternatively, you could provide online facilities to allow customer self-service. However, you would have to move enough customer interactions from the high-cost contact centre channel to the low-cost web channel to justify the fixed cost of the application and the infrastructure it runs on.

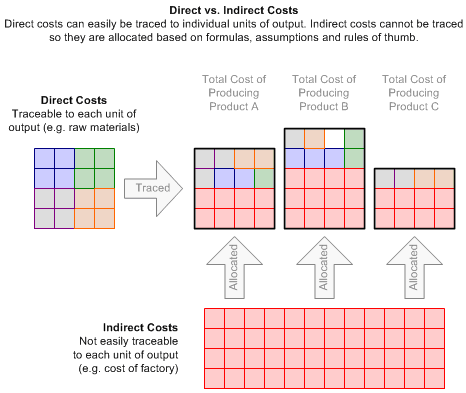

4. Cost Assignment

Knowing what your costs are is not the same as knowing where they are. Costs can

only be managed if you know what is causing those costs.

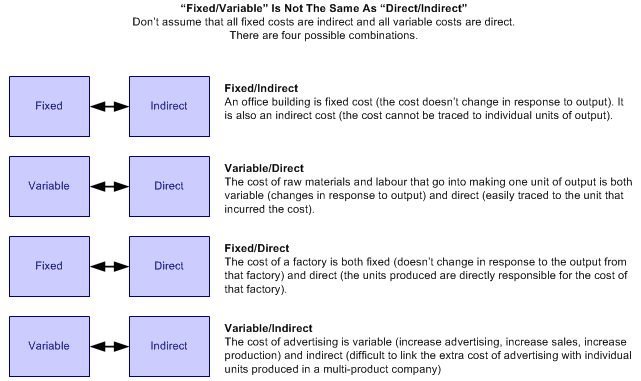

The following diagram illustrates two types of cost (direct and indirect) and how

each is assigned to output [3].

In an ideal world, all costs would be directly traceable to the products/services,

processes and business units that incur those costs. Unfortunately, perfect traceability

is either impossible or not economically feasible (the cost of such traceability

would outweigh the benefits).

Cost traceability projects do not reduce total costs (they merely reclassify them

from indirect to direct) but there is still business value in pursuing such projects.

The business value comes from the fact that if you can trace costs you can manage

them, but if you're only able to allocate then managing costs is impossible. A case

in point is the perennial complaint by business unit managers that IT costs are

too high. The reason for this complaint is two-fold:

- Inaccurate allocation. They feel that method of allocating IT costs is inaccurate

(or even arbitrary) – based on headcount or revenue or some other metric they feel

doesn't accurately reflect their consumption of IT resources.

- Lack of control. Even if the cost was accurately traced (as opposed to arbitrarily

allocated) to their business unit, managers would still be unhappy because they

have no control over those costs. They'll agree that the cost of PC charged to their

business unit is their cost, but they'll dispute why IT mandates the use of a $2000

PC when they can get a $500 PC from Dell.

Cost traceability (or chargeback/showback) projects address both of these complaints:

- Traceability. When costs are accurately traced, rather than arbitrarily allocated,

managers can begin to manage those costs by implementing changes and seeing the

results in the cost figures.

- Control. As in the IT example, managers will not have direct control over some

costs which are traced to their area of responsibility. However, better traceability

opens the lines of communication. Debates (e.g. outsource vs. insource, centralize

vs. decentralize, $2000 PC vs. $500 PC) are far more constructive when discussions

are based on facts).

Project Example: Cost Assignment

Since an organisation's customer contact centre services all customers and all products, poor IT systems could mean that the contact centre's cost may have to be allocated to various product lines based on some arbitrary calculation such as relative sales volume (Product A accounts for half the sales volume so it's assumed it gets half the support calls and therefore should be responsible for half the cost of the contact centre). Such cost allocation may not reflect reality.

This situation would be improved with the deployment of a new call centre management system. If the system lets you time calls accurately and record which products the call was about it would then be possible to accurately trace contact centre costs to the products that incur those costs.

Incidentally, tracing costs to customers, not just products, is also a good idea as it will allow managers to work out the lifetime value of customers (highest revenue customers may not be the most profitable if they are costly to service).

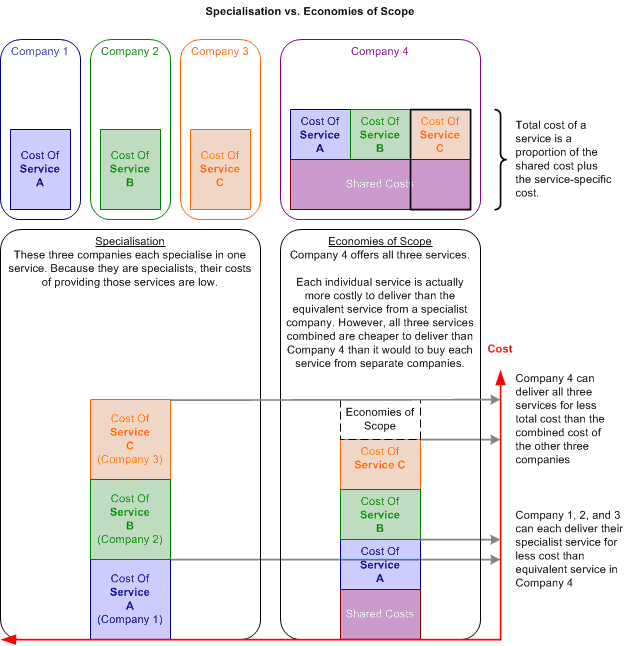

5. Economies of Scope

Economies of scope are cost advantages that result from sharing costs across multiple

products/services. Put another way, the cost of the whole, is less than the cost

of the individual parts. Economies of scope is illustrated below

Project Example: Economies of Scope

Deploying collaboration and knowledge management tools allows people in different areas of the business to join forces and offer a unique product. Management consulting companies are experts at generating economies of scope. They package up their internal knowledge and expertise into numerous service offerings. When clients engage these consulting companies they aren't just paying for the consultants that walk through the door – they are paying for the collective knowledge of the entire consultancy.

Endnotes

[1] There is also a third type of cost: semi-variable. These are hybrid costs that have both a fixed component (which doesn't change with output) and a variable component (which does change). An example of this would be a phone bill where you pay a fixed monthly access charge and then variable call costs on top of that (the more calls you make, the more you pay).

[2] The process by which management analyses cost structure relative to expected volume is called Cost-Volume-Profit Analysis.

[3] The distinction between direct and indirect costs is simplified for clarity. In reality there are four types of costs as illustrated below: