Customer Value and IT Project Evaluation

"The great part of the miseries of mankind are brought upon

them by false estimates they have made of the value of things."

Benjamin Franklin

- Organisations exist to provide value to their customers. Customer value-add should be included in the assessment of proposed IT projects.

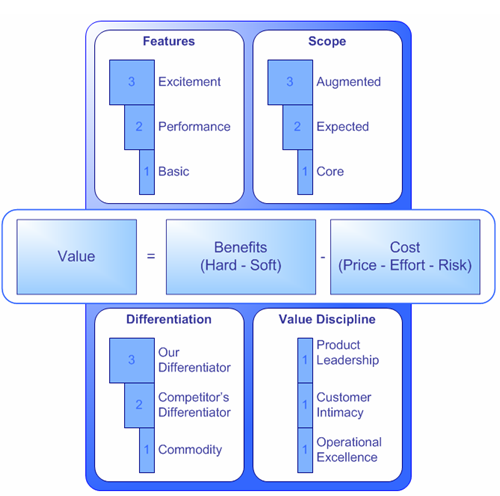

- Value is a nebulous concept but it can be operationalised by breaking it down into four components: features, scope, differentiation and value discipline.

- By scoring each individual component, it is possible to produce an overall score for an IT proposal, which in turn allows competing proposals to be compared and ranked.

Organisations ultimately exist to provide value to their customers. This is true whether the company is government-owned or private, for-profit or not-for-profit.

This article operationalises the concept of value by breaking it down into four parts and assigning comparative weights to each part. This simple framework can be included in the suite of tools used by the governance group responsible for assessing and prioritising IT projects. The framework can be used:

- For the initial triage of incoming project requests. Incoming requests often contain very little information so a decision on whether the proposal justifies further investment is made on gut-feel. This simple framework can put some rigour around that decision-making process.

- During business case development. In addition to quantifiable and tangible financial benefits, all business cases include non-financial benefits such as 'improved customer satisfaction/loyalty'. In many cases these are motherhood statements which are often pasted from one business case to another. This framework allows business case authors to describe nebulous customer benefits in a more structured way.

Value Defined

Value is defined simply as 'benefits minus costs':

The total benefit is comprised of:

- Hard benefits, or what the customer experiences. This includes quality of products, fast delivery, accurate billing, convenient access, clean rooms etc.

- Soft benefits, or what the customer feels. This includes such things as the friendliness and helpfulness of hotel staff or the prestige that comes with owning an expensive or exclusive product

The total cost is comprised of:

- Price. This is the total cost of ownership, not just the initial cost. It includes ongoing costs (e.g. service and repair, consumables) plus all associated costs (e.g. customers will include the cost accessories into the cost of a mobile phone).

- Effort. People that are cash-poor will focus on price, whereas people that are time-poor will focus on effort. For example, many people wouldn't consider changing their phone unless they could transfer their contacts and calendar automatically.

- Risk. This is a hidden cost but it is nonetheless an important part of the value equation. The concept of risk/reward is ingrained in people's psyche, so high risk brings with it the expectation of high reward (i.e. benefits). High risk with little benefit means low value. Risk can be both tangible (e.g. financial loss) and intangible (e.g. loss of face) and it doesn't matter if risk is real of perceived because perception is reality.

This value model works just as well for government departments. If a government department allows me to receive bills electronically and pay them online, they create enormous value:

- The hard benefit is convenient access

- The soft benefit is my feeling that I'm helping the environment by saving paper and the feeling that my tax dollars aren't being wasted on postage, paper shuffling and data entry.

- The effort is reduced because I don't have to write a cheque and post it or sit on-hold trying get through to the call centre to pay my bill.

- The price may be reduced if I get a discount for electing to use electronic billing.

When thinking about value, it's important to think about both costs and benefits. For the purpose of this framework however, the distinction is irrelevant. Whether you classify 'easy to use' as a benefit or a reduction in cost (effort and/or risk), the end result is the same: greater customer value. So for the rest of the article, the term 'benefit' means both cost reductions and benefit increases.

Four Components of Value

To help operationalise the concept of value we can break it down into four components:

- Features

- Scope

- Differentiation

- Value discipline

Features

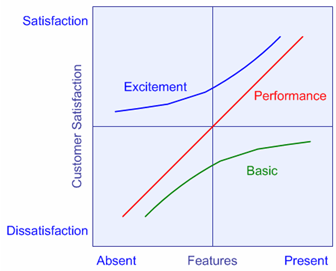

Features fall into three basic categories [1]:

- Basic features are 'must-haves'. Without these fundamental features, customers will decide that your offering has no value at all. For example, when you buy a laptop you expect it to have a battery so that you can travel with it.

- Performance features fulfil customers' explicit needs and are used by customers to differentiate between competing offerings. The higher the performance of an offering, the more value. For laptops, this would be things like processor speed, memory, weight and screen size.

- Excitement features fulfil customers' latent needs. Since customers weren't aware that they wanted these features, they didn't used them in deciding between competing offerings. Once offerings emerge with these features they quickly become 'performance' features because competitors scramble to catch up. Ongoing innovation is essential for creating a steady stream of excitement features to keep ahead of the competition. For laptops, quick booting is an excitement feature.

Everyone understands the concept of features as they apply to tangible products but services also have features. For a courier company, a must-have feature is pick-up of parcels from the office, a performance feature is timeliness of delivery and (until recently) an excitement feature was parcel-tracking (although this has now become a performance feature)

Scope

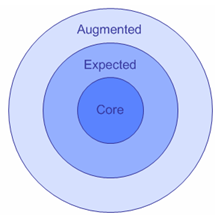

Marketers have long understood that customers don't buy whatever products or services you're selling – they buy the "whole product". The whole product is divided into three layers [2]:

- The core product is whatever product or service you're actually selling – the thing that appears on the invoice. In the case of hotels, for example, customers buy hotel rooms.

- The expected product includes the core product plus everything else that customers expect to be part of the deal. For hotels, this includes room-service, laundry service and Internet facilities.

- The augmented product is the expected product plus anything else that differentiates the offering from the competition. The augmented product shouldn't be confused with excitement features. The augmented product includes the entire value network and ecosystem around a particular product – not features on the product itself. In the case of hotels, videoconferencing facilities, multi-lingual concierges and chauffeur-driven limousines are excitement features, but the augmented product includes such things as tie-ins with frequent flyer-programs and cross-promotions with credit card companies. Similarly, Apple's success with the iPhone wasn't due solely to the excitement features on the phone itself, but rather the augmented product, which includes an entire ecosystem of accessory manufacturers and application developers.

Organisations looking to win in the market should follow Apple's example and compete at the product-augmentation level. Core products are more or less commodities, and competition in expected products is the realm of 'me-too-ism', where every move is met with immediate, and usually identical, countermeasures. But the augmented product is where organisations can differentiate and achieve a competitive advantage.

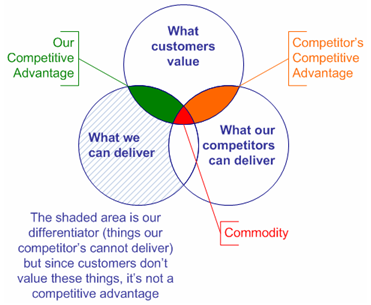

Differentiation

Competitive advantage comes from differentiation. But while we're trying to differentiate ourselves from our competitors, our competitors are trying to differentiate themselves from us. This competition leads to three possible scenarios:

- Commodity competition is where we compete to deliver value in areas that our competitors are equally capable.

- Attacking a competitor's differentiators is a defensive strategy designed to nullify our competitor's strengths so that the value of our competitor's offering is reduced in the customers eyes.

- Leveraging our differentiators is an offensive strategy designed to magnify your strengths to deliver value in areas that our competitor's cannot, thus leading to a sustainable competitive advantage.

There a lots of different differentiators between organisations but customers only care about a subset of them, and it's those differentiators that you should attack in your competitors, and exploit in your organisation.

Value Disciplines

In their best-selling book, The Discipline of Market Leaders, Treacy and Wiersema describe three value disciplines:

- Operational excellence is about "providing customers with reliable products or services at competitive prices and delivered with minimal difficulty or inconvenience." The focus is on efficient execution, high quality and low price.

- Customer intimacy means "segmenting and targeting markets precisely and then tailoring offerings to match exactly the demands of those niches". The focus is on long-term customer relationships and exceeding customer expectations.

- Product leadership involves "offering customers leading edge products and services that consistently enhance the customer's use or application of the product, thereby making rival's goods obsolete." The focus is on design and innovation.

According to Treacy and Wiersema, it's unlikely that one company can excel at all three disciplines, so companies should focus on excelling at one discipline and meeting industry standards in the other two. While this may be true for business strategy as a whole, it is possible for IT projects to add customer value in all three disciplines simultaneously. A recent example is the growing number of companies that are adding mobile phone applications as an additional customer contact channel. These projects add value across all three value disciplines.

The Value Framework

The completed value framework is illustrated below:

The framework includes scores as follows:

- Features: excitement features (3 points) add more value than performance features (2 points), which in turn add more value than basic features (1 point).

- Scope: augmented products add more value than expected products, which in turn add more value than core products

- Differentiation: exploiting our differentiators adds more value than reducing the advantage our competitors get from their differentiators. Commodity competition adds the least value.

- Value Discipline: Each of the disciplines has been weighted the same, but the more disciplines that a project delivers, the more value is created.

The Framework in Action

When IT receives a proposal it can be scored as follows:

- Score each benefit listed in the proposal by assigning it a score for each of the four components. The maximum score for any one benefit is 12 (excitement feature, augmented product, focussing on our differentiator, and all three value disciplines). The minimum possible score is zero.

- Add up the individual scores for each benefit to arrive at a total score for the proposal.

- The total score should then be factored into the overall assessment of the proposal.

Not all project proposals will have a direct impact on customer value. In typical organisations most projects will be internal enablers. Nonetheless, even these projects will have an impact on customer value, albeit indirectly. The scoring system can be modified to give greater weigh to benefits that add customer value directly, than to benefits that add value indirectly.

Conclusion

Customer value-add shouldn't be the only criteria used in evaluating IT projects. However, if organisations exist to create value for their customers, and IT Departments exist to help organisations, it stands to reason that the project evaluation process should include a discussion of the project's likely impact on customer value.

References

- [1] These categories are from Kano models but numerous similar classification schemes exist. For example, Herzberg (motivators, hygienes), Cadotte & Turgeon (satisfier, dissatisfier, critical, neutral), Oliver (monovalent satisfiers, monovalent dissatisfies, bivalent satisfiers, null relationships), Losa (basic, plus, key, secondary), Brandt (basic, attractive, one-dimensional, low impact)

- [2] Adapted from Philip Kotler's original model which has 5 layers (core product/benefit, base product, expected product, augmented product, potential product).